01.24.22Writing and the Athlete, Part 1

Writing is a profound tool for thinking and learning. “The discipline of writing something down is the first step in making it happen,” noted Lee Iococca. To write it is to prioritize it; recall it to your attention; restate, elaborate on and clarify the idea. All these things build memory and understanding. Think it and you will probably forget it; write it and you’re likely to remember.

Writing locks it down in memory but it also often unleashes an idea. The poet W. H. Auden said that he never knew what a poem was going to say until he had written it. Discovery often results from putting it down on paper.

Writing, I think, is untapped for athletes– it could and probably should play a much more significant role in their life and learning. So this is the first of (at least) two posts about the potential of writing for athletes. The second will look at the role writing might play in the growing portion of time top athletes spend studying video and engaged in other classroom type tasks. But in this first part I’ve tried to reflect about how writing could be a useful part of daily on-the-field training.

* * * * * *

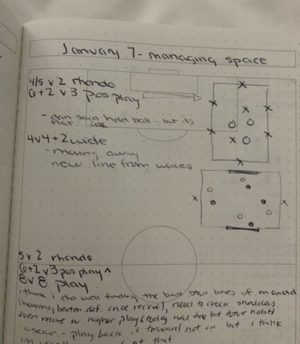

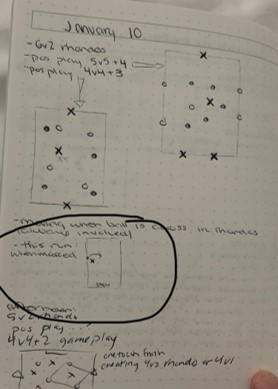

My daughter has spent January training with Todd Beane and co at TOVO Academy. One of the first things that struck me was that they keep journals and write after training. In part that’s because Todd’s goal is to build complete players in the broadest sense, and reflection and self-awareness are key parts of that. But the writing they do is more than journaling of the “here’s how i felt; here’s how i did” variety. (Not that that’s a bad thing. Yaya Toure apparently kept a journal of every game and training; perhaps that’s why he was such a perceptive player and teammate). It sounded surprisingly analytical so I asked Todd to send me a few examples of what players wrote. Here’s one of them:

What struck me right away was the use of diagramming. I’d never thought about that. But it struck me that this helped players both to remember and be attentive to the spaces (physically, visually) as they train- to see the design through their coaches’ eyes. It caused players to, as Todd put it, “lay out a spatial relationship formed of triangles and diamonds.” It’s reinforcing the building blocks (“geons” if you’ve read Coaches Guide to Teaching) of spatial understanding. Todd compared this to architectural drawings. Players are sketching the principles of space that build up to 11v11 play and positioning more clearly.

It’s also worth nothing had the players marked up the diagrams. Words plus images is a very powerful combination. The visual increases the amount of knowledge players can process and remember (see Oliver Caviglioli’s Dual Coding for more on this) and the language builds understanding. “Diagrams + words keeps a better record of the experience,” Todd said.

My daughter had one page where she added an arrow to a diagram and wrote: “this run when marked…”

She’s linked her understanding of space with her desire the change her actions within it.

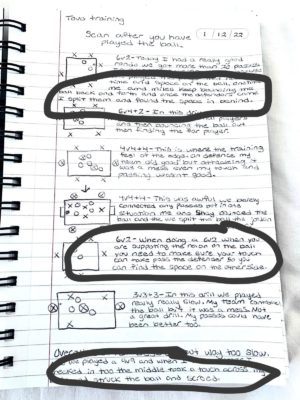

Here’s another example from one of Todd’s players (i circled some things i thought were interesting)

At the top the player is reinforcing a moment where the coaching point (move the ball to move the opposition) created a memorable outcome: “[We] kept bouncing that ball back and forth and once the defenders came out I split them and found the space in behind.” Remembering and memorializing a break through like this will help prioritize it in memory and just maybe lead to it being replicated.

In the second example the player is restating the key principle: “need to make sure your touch can take [you] past the defender so you can find space on the other side.” Again this is an idea that perhaps was a notion vaguely installed in memory that is now clear- crafted as a sort of personal principle of play.

A tiny last thought. “A lot of my guys,” one coach of professional athletes said to me, “they weren’t always successful in school. They don’t especially like to write. Many of them would struggle to write in a journal.”

In many ways I think people learn to make writing part fo their lives because they come to find pleasure or value in it. Even at the professional level, even with adults, I think we can change behaviors and grow people’s capacity off the field too. And I suspect that a lot of athletes might surprise their coaches in a positive way. But even in the worst case scenario- even if it were true that you really did have a player who simply could not write, the idea of diagramming creates a powerful and useful alternative way to process ideas and might even over time give the athlete and opportunity and an incentive to add language in small pieces- this would be especially likely if they found the writing valuable and useful.