05.22.20Excerpt: The Coach’s Guide to Teaching

I’m closing in on my manuscript deadline on my new book, The Coach’s Guide to Teaching. The sense of urgency–some might call it desperation–is palpable. But I’ve just finished Chapter 4, which is about Checking for Understanding. Here’s an excerpt to whet your appetite. Hope you enjoy

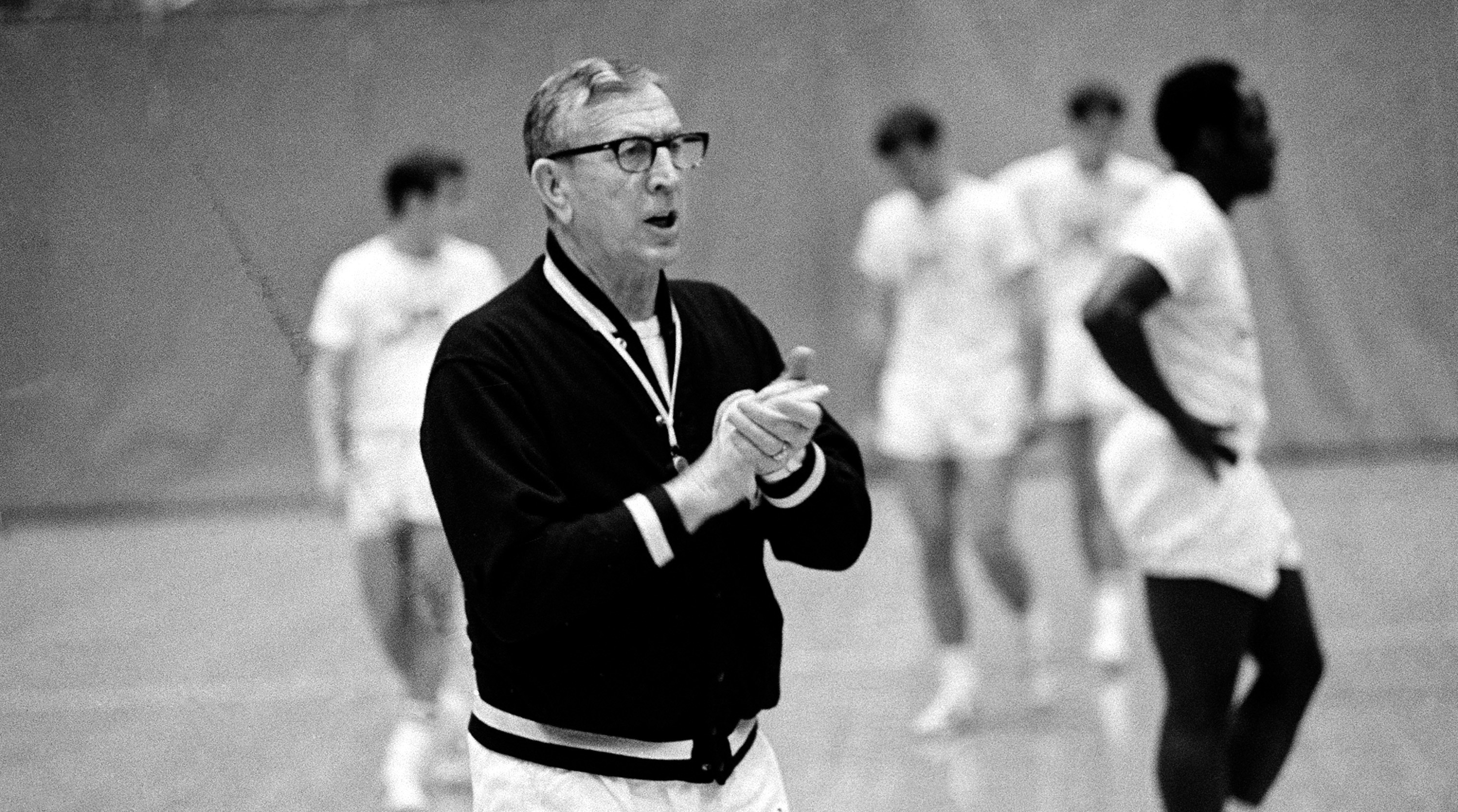

John Wooden was among the greatest coaches of the 20th century. No doubt he was among the winningest, but he remains among the most admired and most quoted, too. Wooden’s stories, aphorisms and principles are often afforded nearly canonical status and retold like parables from the gospel:

- The story of how he began the UCLA season by instructing his players in how to put on their socks reveals that we should begin at the beginning- and perhaps that the beginning starts earlier than we think.

- The tale of his response to Bill Walton’s announcement that he didn’t want to cut his hair in accordance with team rules–Wooden praised Walton for standing up for his convictions before adding, “and we’re sure going to miss you around here, Bill”—reminds us that the test of our principles is whether we apply them to our best players and when they result in our losing games.

Perhaps because he was a teacher before he became a coach, his wisdom about the teaching side of the craft is practical, wise and, so far, mostly, timeless. Of all his adages and sayings, the one I find most useful is his definition of coaching (and teaching). Teaching, he said, was knowing the difference between “I taught it” and “They learned it.” No matter the setting, bridging the gap between those two ideas is at the core of what teachers do and often the greatest challenge of the job. Certainly it is in coaching sports.

Any teacher seeks to present a concept for study as well as she can—clearly, memorably so that as many students understand as much of it as possible, but no matter how good the initial instruction, learning will break down. Gaps will emerge. Often our first response is to try to establish whose fault that is, but mostly it is what happens when people try to teach and learn things, especially when they try to teach and learn things that are challenging and complex. Quite possibly the greatest insight from Wooden’s adage is its calm presumption that the gap is inevitable. It is not a question of whether it exists but how we deal with it. Teaching, he proposed, is not eliminating the gap; it is understanding it. It is the coach’s job not to offer a perfect initial explanation but to seek out and anticipate the ways athletes will struggle. To be a great coach is not just to have a deep knowledge of the zone press, not just to be able to translate it to players, but to see what goes wrong as they try to learn it. This process is called Checking for Understanding and is as challenging to master as it is important. Among other things it requires coaches to shift how they prepare to teach and even how they observe when athletes are training.

The Trials of Looking

In chapter 1 I discussed the critical role perception plays in decision making for athletes. To perceive well is not only necessary to good decision-making, in many cases the line between perception and decision blurs. An athlete reads the first incipient cues that suggest how her opponent will move and is already acting on them in real time—we call it anticipation; it is as if she knew what her opponent might do–and she succeeds. Or, alternatively, her eyes are elsewhere when the critical information (they are pressing!) emerges and so she fails to react. The perception and the decision are hard to separate. Athletes can be lucky once or twice, but in the long run their decisions can never be better than their capacity to see and understand what is happening around them.

It is the same for coaches. A coach’s ability to teach and develop athletes is limited by his or her ability to perceive what they are doing during training- a task that is far from simple. We presume that seeing is all but mechanical–you direct your eyes toward an event and become aware of what is happening–but in fact this couldn’t be farther from the truth. Seeing is technical, challenging, and subjective, a skill you might argue, certainly a cognitive process far more than a physiological one. All of which is especially important to recognize because the ability to see accurately is a coach’s first skill.

Here’s a tiny example of what I mean: a stoppage at a recent training led by a very good young coach. He was using passing patterns to familiarize his players with common movements in buildup play, and he noticed that girls were often static when waiting to receive a pass. He paused them briefly and, standing next to a central midfielder, said:

“Girls, when you see the outside back receiving the ball, you know that you are going to be one of her primary options, so you don’t just have to be ready to receive the ball, you have to create separation so that you make an opportunity. That means a movement like this [he demonstrated checking away] to take your defender away-and then come back to the ball. As we work on these patterns, I want to see you making movements like that. Every time. Check away, then come back for the ball. Go!”

By the basic rules of feedback (see chapter 3) his feedback was strong. He explained one idea, demonstrated and described the solution clearly and quickly, then gave athletes a chance to try it right away. But he failed to do something so simple that most coaches don’t even realize when they fail to do it. He failed to observe. He positioned himself well afterwards, he looked at the girls cycling through the patterns, but after he said, ‘Go!’ eight out of the next ten girls receiving the ball failed to make a movement like the one he had described. There was no checking away. No checking at all, and somehow he did not notice. He was looking but not seeing. Perhaps he simply assumed they were doing it and was only half-looking. Perhaps he was thinking about something else. But for whatever reason, play went on without correction, and his next stoppage addressed a new detail.

He had taught it, but they had not learned it. Or even done it, really, and it’s not hard to imagine a Saturday, not too far down the road, where at halftime he would say with some urgency, and perhaps even frustration edging into his voice, “Girls, we’re static. We’ve talked about using our movements to create space to receive. We’ve got to be creating space.”

In that moment he will be describing John Wooden’s gap to them: Girls I taught you how to create space, but you have not learned it.

There are a wide range of reasons why athletes would not be able to execute something they did in practice during competition, and I have tried to discuss many of them elsewhere in this chapter and this book. There could have been insufficient variation and spacing of retrieval practice so that athletes forgot what they did a few times in training on game day. The training environment might have never progressed to a complex enough setting to prepare athletes to execute under performance conditions. Athletes might have failed to read perceptive cues telling them it was the right time to execute a skill they know how to do. But in this example, I am describing something much simpler than the failure of a skill to translate from practice to game. The perils of observation are such a coach can ask players to do something plainly observable, and the athletes can fail to do it, right then and there, only seconds later, and the coach will fail to see it.

To remediate the learning gap the coach might have said something like: “Girls, I didn’t see the sorts of movement we discussed there. Let’s try again.” Perhaps he might have added, “I’ll watch ten of you now and say “yes” or “no” to show whether I saw you check away.” Perhaps he might have said, “Girls, we’re struggling to make those movements and I suspect it’s because we’re trying to make them too late. Try to start them a little earlier and see if that helps.” Perhaps something else. But a coach can only respond to errors that he sees. First you have to perceive the error, and surprisingly, that is the step where the process breaks down far more often than almost anyone would suspect.

In fact, if there is one thing I can offer in this chapter to help you teach better it is to urge you to resist the temptation to judge this coach. Some version of this story has undoubtedly played out in one of your recent trainings whether you coach 7-year-olds or professional athletes, whether you are a new coach or an established and respected veteran. There is a part of you that does not believe this, but I am 100% certain it is true. This is the remarkable part of the story. With some regularity the athletes you train simply do not do what you have asked them to do, and you fail to see it. If someone showed you a video afterwards, they could easily point it out to you. You asked for the combination to end with crosses on the ground. Count the number of crosses on the ground. Or, you asked them to practice using both feet. Count how often they use their left foot. What was hidden in the moment you were coaching would now be obvious. Players were not striking crosses on the ground. Almost nobody used their left foot. You fail to see what was right in front of you, therefore to fail to understand your athletes and their struggle to learn. We all do this. We are all, with some frequency, the coach I have just described. The only question is whether we will have the humility to accept this. Only then can we take steps to change it.

Science tell us that we see only a fraction of what’s right before our eyes and there are a variety of reasons for this. One is attention. We miss things because we’re not concentrating on looking. We’re looking passively. Observing carefully to see what 16 athletes are actually doing at a complex activity is hard work, and the brain is designed to only work hard when it must, when we force it to. What’s more ‘observing’ doesn’t feel like coaching so we may be unlikely to focus on making the effort it requires if we don’t see it as a critical task. Much of the time we should be observing intensely, we feel like we should be saying something or at least setting up some cones. Instead of really looking we’re thinking about what we’re going to say or do next or who’s going to start on Saturday. But looking well takes single-minded concentration. We have to see it as a task. We have to force out minds to do it actively.

There are technical problems to overcome as well. Your optic nerve connects to the back of your eye in a spot about fifteen degrees to the side of your center of vision, for example. There are no receptor cells there. Your cortex receives an incomplete picture of the world around you. To compensate, it fills in the gaps with what it thinks it’s likely to have seen in the blind spot. It uses other sources of information— your other eye, what you saw when your eyes looked in the space you cannot see a few moments ago. The brain does this so seamlessly that most people never even know the blind spot is there[2] but it is shockingly large. We often say that we see the world as we imagine it to be and mean that metaphorically, but it is often literally true as well. What we think is there is different from a person standing beside us.

Our perception is subjective and immensely fallible. We just don’t want to believe it’s true. As Chabris and Simons put it, “We are aware of only a small portion of our visual world at any moment” but “the idea that we can look but not see is flatly incompatible with how we understand our own minds.” We can only fix the first part if we fix the second. If we want to be better at developing athletes, we have to take the task of seeing them as they learn far more seriously.

Let’s return for a moment to the

session where the girls failed to make the checking movement their coach had

asked them to make. The technical name for not seeing what is right before our

eyes is ‘inattentional blindness,’ and one reason I saw what the coach did not is

that, I had been discussing the

challenges of observation with a group of coaches just the day before. I walked

in the door expecting it to happen. I saw it not because I am especially

perceptive—I am as likely as anyone else to miss what is right before my

eyes—but because I was prepared, and this Chabris and Simons tell us is the key

to seeing better. “There is one proven way to eliminate inattentional blindness,” they write. “Make

the unexpected object or event less unexpected.”

[2] Any cognitive scientist can prove it’ presence in seconds https://www.eyemichigan.com/what-is-a-blind-spot-how-do-i-find-it/