02.13.21Ben Kamara-Adams: How to Coach a Rondo

Ben Kamara-Adams is a Pre Academy Coach at Shrewsbury Town FC in England and an ambassador for Albert Puig’s APFC soccer. He and I met last year when I did a workshop for the club and have kept in touch as he spends a lot of time thinking about how best to develop players through his teaching. He shared some thoughts about rondos on social media a few weeks back and I was struck by how well it demonstrated both teaching methodology and clarity about the knowledge he was trying to build in players. I asked him if he’d consider writing a guest post and this excellent reflection is the result.

The rondo might be the single most commonly used training exercise for football players around the world. But from my experience most coaches don’t use rondos nearly as well as they might. Often a rondo is simply done as a warm up, an activation exercise. If there are “rules” they are to merely to add a two touch limit or to set a goal of “7 passes.”

But the rondo is so much more than that. “All concepts in soccer are inside of a rondo,” Albert Puig likes to say.

One of the things he has taught me is to label, isolate and focus on key principles of the game. This helps young people identify learn and remember these actions. In this post I will discuss here how you can coach a rondo with some of these concepts as your objective.

Before I describe the individual concepts, there are two general rules for rondos that you must follow:

- Rondos must always be practiced at game speed and intensity

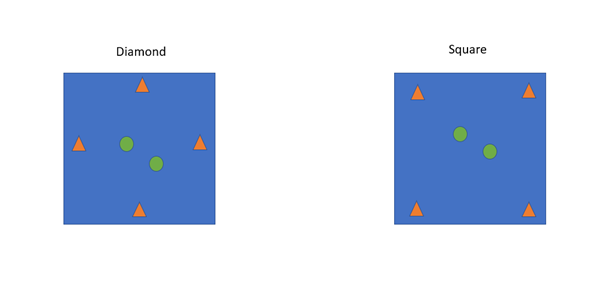

- A 4 v 2 rondo must be in the shape of a diamond and not a square. This is to ensure that the passes are diagonal. I will explain the benefits and objectives of this later. It also often helps players conceptualize concepts if you make your diamond directional, with a defensive midfielder at the base and a striker at the top.

Here are my favorite game-related technical principles to build a rondo around:

- Head up

- Back Foot

- Break lines

- Diagonal passes

- Opposite movement

- Ball never stops

Head up is the most important of them all. Teaching players how to see the game will stand them in great stead in every match they play for their entire career but how often do you see a session built around it? It is usually reduced to reminders of head up, check your shoulders and scan.

Here’s how to teach head up in a rondo.

What to teach when it comes to head up

A player should be able to keep their head up before, during and after receiving the ball. This can be taught to u8s all the way up to u18s. Once I see the ball coming towards me—or even while I am anticipating that it might–I must look for my next pass. I mustn’t look down whilst receiving the ball and I must keep my head up while making a decision.

Planning a 4 v 2 rondo with head up as the focus.

Organisation – 10 by 10 (or 10 steps in each direction) diamond.

Objective – Playing with the head up, looking for the next pass before you receive the ball.

Structure – start as a 6 v 0 rondo, passing with the head up practice, then introduce 1 defender to make it a 5 v 1 and finally introduce a second defender 4 v 2.

Error planning: What will most likely go wrong – Players will keep looking at the ball; they will stare directly at the person who has passed them the ball; they will improve without pressure but as I introduce a defender they will revert.

Timings and coaching points – 90 seconds each block.

Start with a demonstration of what it should look like.

First block 90 seconds – Focus on having your head up; no interventions.

Second block of 90 seconds – Discuss what went wrong and demonstrate the correct technique. I have to look for my next pass. I mustn’t watch the ball at any point.

Third block of 90 seconds – Challenge them to do it with a bit more speed and keeping their head up 80 percent of the time. If you hear me say “yes” I like it. If you hear me say “up” you know you can still do better.

Fourth block of 90 seconds – Introduce a defender. I reiterate: I would rather you lose the ball with your head up than succeed with your head down. I explain that a ‘thinking touch’ where they control the ball and then lift their head takes 1 or 2 seconds. In football, that might as well be two hours.

Fifth block of 90 seconds – Do it again focusing on decisions. Were they quicker? Was it easier?

Sixth block- Introduce the second defender.

At the end of this I will decide what comes next based on their proficiency. I may get them to go back and repeat if they are struggling, or I may start to add more details. And I’m planning on doing it again tomorrow. And the day after. 80 percent of the value in learning comes from 20 percent of the ideas. This is one of those ideas.

The Other Concepts

It’s worth spending time really mastering head up because if players can’t do it, the other concepts are difficult to teach- and possibly not worth teaching. The purpose of being ‘side on’ or having a forward-facing body profile is so that you can see more of the pitch. If your head’s not up there’s no benefit to those things. Similarly without your head up you won’t know where the defenders are and will not be able to use the back foot to control away from pressure.

For purposes of brevity I will condense the six remaining concepts into one practice. But my purpose is to show how you can progress a rondo, week-in, week-out, and teach actionable things.

What is the back foot?

Coaches at grassroots and academy level tell kids back foot, back foot all the time. One day I asked some kids, “Do you even know what the back foot is?” One said it was their left foot, one said it was their heel, one said it was their strong foot. You can simply convey this concept to kids by saying the back foot is the one furthest away from the ball. What foot is furthest away? It may be their left or right, then ask them to pivot. Now what foot is furthest away?

Why the back foot?

Using the inside of the furthest away foot we can control forward quicker. We can also control away from pressure.

What is a ‘line’ in football?

Imagine Iniesta on the half-way line. That is a line. Each individual player creates a horizontal line. Picture Iniesta standing on that same halfway line with Luca Modric. These are now two players standing in the same horizontal line. In a rondo the two players in the middle are opposition centre midfielders. One of those midfielders has gone to press our striker. The other midfielder is in the centre of the rondo waiting to see if he can intercept the next pass. If the winger on the right stands in the same horizontal line as him and has the correct body position, he can receive a pass on his back foot and control in the space behind the defender. This is what we call beating the line with your first touch.

Break Lines

One of the best things to teach in a 4 v 2 rondo is a pass that breaks lines, either via first touch as I described above or via a pass that splits defenders. This is a great pass because you have now effectively eliminated these two opposing players leaving the striker alone to play forward or facing less players. The opposing players also have to turn around which allows the receiver of the pass in a rondo more time and space.

Diagonal Pass and Opposite Movement

‘Opposite movement’: A defender gains the advantage when he can see both the ball and the player. If teammates without the ball move diagonally away from a teammate with the ball, they practice being in a channel away from the opponent’s eyes. The opponent cannot watch both the ball and us. This is one of the most important off-the-ball habits in football.

Placing the rondo in a diamond is key to this. In a square you have limited room for movement. In a diamond players can move up and down to break lines and reduce the defender’s knowledge of their position.

In a 4 v 2 rondo and in a game. When a teammate is under pressure, we must stand close to them to offer a line of support and ensure we retain possession. So, in a rondo if the defender is under pressure the left winger can come as far down the 10 v 10 square as he can. In a match this could be Gerard Pique under pressure from Benzema and Busquets coming down in the same horizontal line as Pique give him a supporting option.

But when this happens the other winger can move in the opposite direction–as far up the rondo square as possible. This ensures that we will maintain a diagonal line for a pass away from pressure and that breaks lines. This idea is called ‘opposite movement.’ One player down and the other up, with the two players off the ball reading one another’s movements as much as those of the player on the ball.

Ball Never Stops

In a rondo one of the basic rules is: Never stop the ball. Do not control the ball in front of you, always move it in a different direction: away from pressure in many cases but towards pressure—to lure defenders away from the teammate you’ll pass to–if you have time and space.

Pep Guardiola says that the object of the pass is not to move the ball but to move defenders. If you keep the ball moving and circulating, you never give the opposition players time to set and reshape.

Below is another plan I did for the u13 shadow squads.

Building on the Head Up concept with the same 4 v 2 rondo.

Organisation – 10 by 10. 10 steps each way. Or 10 yards each way.

Objectives – Keeping the head up, Using the back foot. Breaking lines

Coaching points – Instead of just looking for our next pass we are looking for a pass that breaks lines and eliminates defenders. When we see the ball coming, look around and identify: can you use the back foot to control forward, pass to beat lines or must you control away from pressure.

What most likely will go wrong?

They will force a pass to break lines. They will play safely around the defenders and not make that clinical pass through the middle. They will control with their front foot when they could have progressed forward, beat a line or controlled away from pressure. They will control towards pressure.

Structure – 4 v 2

Timing and interventions – 90 second blocks.

First block of 90 seconds – I will demonstrate a break the lines pass and will explain what it is. I will then explain that I want to see them look and make as many of these as possible.

Second block of 90 seconds – If they have been forcing the pass, I will tell them to keep the ball moving and make the pass when it presents itself. I will also show how and when they should control on the back foot.

Third block of 90 seconds – In this round I will make stoppages during play. For example, if a pass has come through the opposing player in the same line as you and you have space to control on the back foot with your first touch and play in the other direction but instead, you controlled forward and lost the ball or played it back to the person whom played it to you. I will ask the team what we missed then I will replay the pass with me as the receiver explaining step by step. “If I have the space and the time, and I have had my head up to see his positioning I can do what?” If they don’t get it, I will say receive on what? They should say back foot. And then I will explain how they could beat the player with their first touch.

Fourth block of 90 seconds – Same coaching points but fewer stoppages. I make corrections and reinforce strong execution while they are playing.

Fifth block of 90 seconds – Same again. I will ask them if they see a difference? Are we playing more efficient and quicker?

If You Want to Learn More About Rondos.

I hope this has been helpful. If there is anything you have questions about you can message me on LinkedIn. My name there is Ben Kamara-Adams and my bio should say I am Pre-Academy coach for Shrewsbury Town- or you can look up apfcourses.com or email info@apfcourses.com