06.09.21Erica Woolway: Changes to Our New Online Workshops

Our team has been busy at work preparing our content for our upcoming workshops on Engaging Academics and Building Strong School Culture that kick off, via zoom, next week. Last year at this time, we were preparing to deliver our content for the first time remotely. After a year of leading training online we’ve been to discover that, while we’ll always prefer to be in-person, we are still able to create vibrant professional cultures online that leverage practice in breakout rooms. We’ve learned a ton about building engaging and rigorous PD culture online—and about the fact that we can help a wider range of schools when they don’t have to get on a plane and fly to Nashville or Charlotte for two full days to train with us.

This year, we are especially excited to share our updated content, reflecting our team’s updated learnings, captured in Teach Like a Champion 3.0 which will be coming out in the fall. We’ll be posting a series of blogs about this content, but in advance of our workshops next week, we’d like to share a few of these differences that you’ll see in the training.

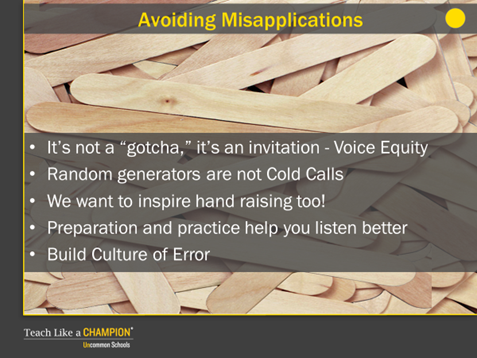

First, both in the new book and in our workshops, we are now much more explicit in calling out the risk of misapplication of the techniques. Here’s an example from Cold Call.

In the past we’ve consistently named that Cold Calling is not intended as a gotcha, but now we double down on the importance of using it positively. In the book and in our new set of workshops, to give another example, we explicitly describe that while using random generators like popsicle sticks can be quite useful at times, it is not to us an example of Cold Calling. It’s often beneficial to communicate intentionality to students. For example, to say: “David, what are you thinking?” tells David that you value his unique opinion and are thinking about his perspective at that moment. To use sticks is to say ‘Anyone can go next. It’s all about the same to me.’ The message of inclusiveness—your voice matters— and voice equity is not communicated by randomness.

We also clarify that while sometimes you may choose to intentionally use Hands Down Cold Calling, that one of the purposes of Cold Calling is actually to inspire hand raising, so if you only use Cold Call with hands down, you miss out on what of its greatest purposes which is in motivating to students to participate.

Importantly, Cold Call, like almost all of the techniques in Teach Like a Champion, benefit from teacher planning and preparation. An awkward and hesitant lead-in to the Cold Calling by the teacher makes students awkward and hesitant, and as a result, Cold Calling is therefore much less likely to build a positive and inclusive culture. Scripting your Cold Call questions in advance (or embedding your Means of Participation into your lesson plans) and briefly practicing a few times before class can help teachers to be more themselves when they use the technique. And of course when you’re thoroughly prepared, it frees your working memory and allows you to listen better to student responses.

A second important shift in our workshops and in 3.0, is the incorporation of cognitive and social science, and DEI research. Again, you’ll be seeing examples of this on our blog over the next few months, but here are examples of how these show up in our workshops:

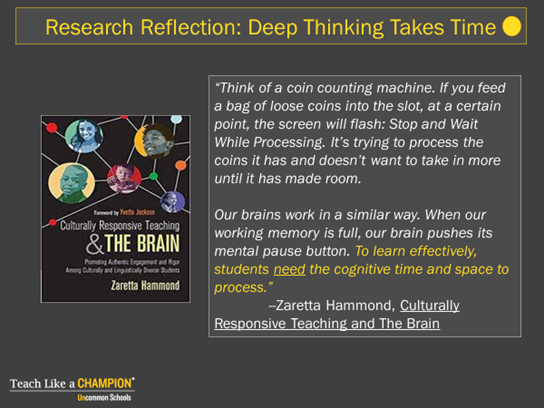

In our discussion of Wait Time, we allude to Zaretta Hammond’s cognitive research that tells us “students need the cognitive time and space to process.”

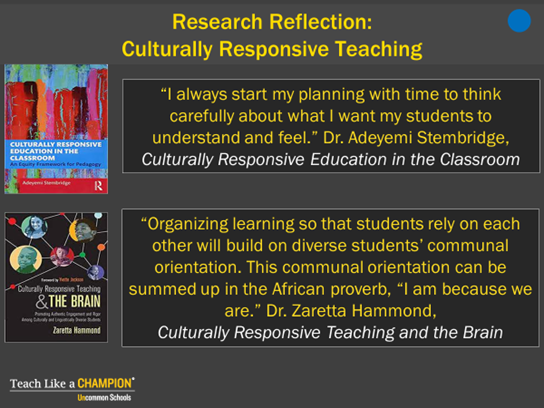

And this slide around the importance of lesson preparation:

Throughout our workshops and in the new version of 3.0, there is an increased overall emphasis on lesson preparation which is also reflected in the research. We’ve even added a session in our Engaging Academics workshop that is dedicated to lesson preparation. While much of what Doug wrote about in the second edition focused on how to plan an effective lesson, 3.0 includes a chapter that “endeavors to shine a light on the methods my team and I have observed teachers use as they prepare to teach their lessons, instead…What’s the difference, you might ask, and why the change?”

Preparation is universal. Not everyone writes their own lesson plan every day. Many teachers use a plan written by a colleague or a curriculum provider. Some reuse a plan they wrote previously. But everyone prepares (or, I argue, should prepare) their lesson before they teach it. If a lesson plan is a sequence of activities you intend to use, lesson preparation is deciding how you will teach it. Those decisions can determine the lesson’s success at least as much as the sequence of activities it uses, but because planning and preparation are readily confused, it’s easy to overlook the latter and think once the plan’s done, you’re ready to roll.

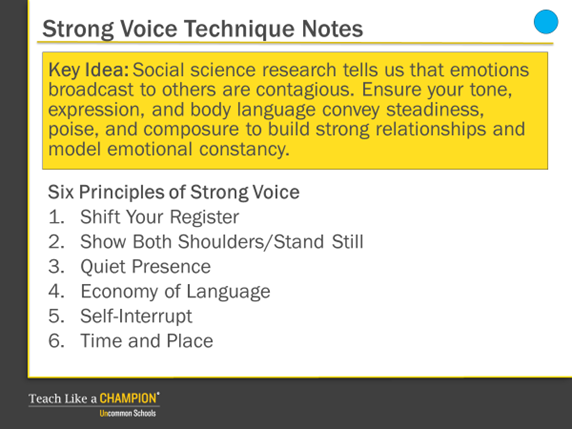

And finally, you’ll notice a shift in some of our language that reflects both the research and risk of misapplication. Here’s our updated notes on Strong Voice for example:

First, you’ll see how the Strong Voice technique is first and foremost embedded in the social science research and how the framing above is different from previous iterations of how we trained on the technique.

What you’ll hopefully also notice above is both what has stayed the same, and what has changed about the language in the techniques. Most notably, while Strong Voice is a critical technique for teachers to master, it is also one that is easily misunderstood, so we begin with some important notes on the purpose and even the name of the technique, which, we almost changed for 3.0, in part because “strong voice” has always been a bit of a misnomer. It is a technique as much about body language as about voice, for example. More importantly, the strength implied is in most cases about steadiness and self-control, about maintaining poise and composure, especially under duress. We describe the chain of reactions that begins with how people read our tone, expression, and body language is long and complex. Strong Voice helps you attend to signals communicated by such factors in your communication as a teacher and use them to increase the likelihood that students will react productively and positively to the things you ask of them. Aligning your tone, expression, and body language signals to the rest of our communication helps you to build stronger relationships, ensure productivity and, especially, avoid the sorts of showdowns that can spiral into negativity.

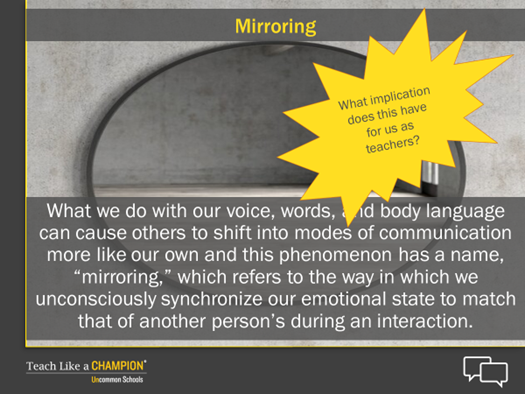

When we’re conversing, we’re not merely exchanging ideas, we’re often shaping the listener’s mindset and emotions. Researchers have found that emotions can spread between individuals even when their contact with each other is entirely nonverbal for example. In one study, three strangers were observed facing one another in silence. Researchers found that an emotionally expressive person transmitted his or her mood to the other two without uttering a word.

What we do with our voice, words, and body language can cause others to shift into modes of communication more like our own and this phenomenon has a name, “mirroring,” which refers to the way in which we unconsciously synchronize our emotional state to match that of another person’s during an interaction. One implication for teachers is that if we can keep our composure, or even noticeably recompose ourselves as things get tense, others are likely to follow. And of course if we lose our composure others are more likely to as well.

When we train on Strong Voice, our coaching often involves helping teachers avoid risk of misapplication and not to come on so “strong” with their Strong Voice—to be calmer and quieter, to appear self-assured, not loud. One potential reason people might try to be more forceful in tone and body language than necessary is the name itself: something called Strong Voice must be about being overpowering, right? Wrong. A composed teacher makes it more likely that students will maintain their composure, will focus on the message, and not be distracted by how it was delivered. Being more aware of your body language and tone of voice and keeping them purposeful, poised, and confident helps you and your students.

So while we toyed with the idea of renaming Strong Voice, we have kept it for continuity’s sake—and chosen instead to add framing to help make sure the purpose is clear. You will notice however, that the language of several of the sub-techniques has changed. Do Not Engage and Do Not Talk Over have been replaced with “Time and Place” and “Self-Interrupt” to better reflect our own guidance by giving clear directions about what to do, as opposed to what not to do. And Quiet Power has been replaced with “Quiet Presence” – better capturing what we mean about the importance of getting quieter and slower when you need students’ attention. Raising your voice will increase the sense of tension in the classroom, especially if you are speaking at a faster pace, too. So, developing your Quiet Presence is an important tool in helping maintain emotional constancy and therefore better build relationships and trust with your students.

So this is just a sampling of some of the changes that we are excited to share in our workshops next week. We have a few seats left if you’re able to join us remotely. If not, we hope to share this content again later this summer so that teachers and leaders feel prepared for the school year ahead. If you’re interested in our training your entire staff remotely in this content, you can also fill out a request form here. We also hope to be traveling soon, so in person trainings may also be an option in the months ahead!

–Erica Woolway