08.01.19Department of Unpopular Opinions: The Skillful Management of Attention is the Key to Success in a High-Tech Society

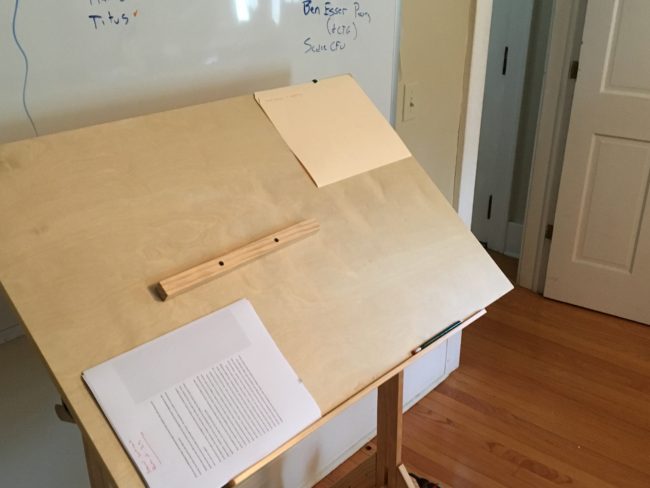

I’m writing this post–at least its first draft–at a drafting table I’ve just put in my office. The desktop slopes steeply–too steeply for my laptop–and that’s the point. Standing here I can’t check email or see ‘what’s up’ in the world via the internet, which I usually justify on the grounds of researching something. I’m forced to sustain my concentration on a single deep task- writing.

The drafting table is one of several life changes I’ve made as a result of reading Cal Newport’s Deep Work, which I picked up because I was concerned abut my slipping productivity. I don’t feel like I am as focused at work, and the (three!) book projects I’m working on seem to be languishing.

Anyway, the book has caused me to reflect not only on my own actions and habits but the actions and habits of educators and schools as well. In this post I’ll summarize the book, and reflect on its relevance in schools.

A summary of Deep Work: Newport argues that the greatest driver of both personal satisfaction and economic value in the work you do is your ability to sustain states of deep concentration on a single task. “To do good physics work,” he quotes the eminent physicist Richard Feynman saying, “You need absolute solid lengths of time … it needs a lot of concentration.” This is true of most knowledge work, and, Newport points out, the ability to produce unique work of merit has never been more highly rewarded in the marketplace.

At exactly the same time it has never been harder to accomplish. Our time and focus are constantly fractured and fragmented and this makes it harder to find and make use of sustained blocks of time in states of deep focus. We’re constantly interrupted by email and text and social media as well as our own desire to ‘check the internet’… I mean ‘research’ something.

Over time this shapes how we function. Day after day of scattered reactivity driven by our inboxes versus sustained effort in thinking about the most important problems in our world results in our losing the ability to sustain the habits of mind that allow us to our best work. It’s a bit like the way we’re losing our ability to read deeply- a topic I recently wrote about that also has direct relevance for schools.

Anyway, I think this is undoubtedly true about me. I feel my productivity slipping. I feel myself losing the ability to do my best work at what I love and value. Thus the un-lap-top-able writing desk and a series of other changes I’m making to my work life (others include taking social media off my phone and setting up blackout times during the day when I am not allowed to look at email).

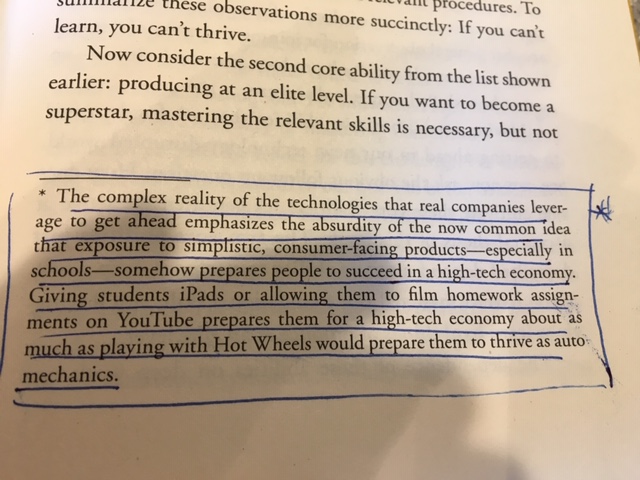

But what about schools? Well first consider this brilliant footnote that gives the lie to the simplistic way that so many schools build “digital literacy” into their daily work. If you want to create value in the tech sector you have to do the deep work of coding and design. Most screen-based school activities don’t prepare students to do this. They just make a habit of distraction:

Frequently, talk of 21st-century skills causes people to install in schools lots of distracting, low-value activities and technology that further fractures time and focus and drives out the enduring and not-sexy, low-tech tasks that are secretly the drivers of the ability to make sense of and manage intelligent machines.

To Newport, who is a professor of computer science at Georgetown, the 21st century-skill that matters is the ability to win in the race between people and machines. AI and automation can do more and more and “most of the intelligent machines driving the Great Restructuring are significantly more complex to understand and master [than the consumer applications that most kids use in school under].” The super-power is being able to do things like understand and write the SQL commands that make sense of the information huge databases gather, for example. These task look a lot like close reading. What they require above all is concentration.

Schools rarely think about this. One of the most useful ideas in the book, for example, is “attention residue”- the idea that when you switch between tasks some part of your brain is still thinking about the previous or next task. You are not fully focused on job one. Teaching people to work on a “single hard task for a long time without switching” is, in other words, one of the greatest gifts you can give a young person. Newport quotes the science writer Winifred Gallagher,

“The skillful management of attention is the sine qua non of the good life and the key to improving virtually every aspect of your existence.”

Do most schools think about limiting focus and distractions and NOT constantly switching activities as highest-value learning environments? They do not. In fact they are probably more worried about “keeping students engaged” through group work or consumer-facing technologies or activities designed to pander to rather than reverse short and skittish attention spans. The overuse of group work might be an example in some cases.

But if Newport is right, it’s haves and have nots in the knowledge economy and being in the haves “requires that you hone your ability to master hard things. And because these technologies change rapidly, this process of mastering hard things never ends: you must be able to do it again and again, quickly.”

The ability to pay attention is the core skill behind “the mechanics of producing at an elite level.” And the ability to focus and concentrate in the face of hard work is a skill built up over time in students not by giving in to their attention fragmentation but by actively seeking to counteract it. Ironically that almost assuredly requires long stretches of time away from screens and doing hard things, solo. That, inconveniently, might just be the thing that will give students the most agency in an automated society.