09.25.19How ‘Standards’ Work In Our New Reading Curriculum

In her new book, ‘The Knowledge Gap,’ Natalie Wexler writes, “Cognitive scientists have known for decades [that] the most important factor in reading comprehension is not generally applicable skills like finding the main idea — it’s how much knowledge and vocabulary the reader has.” We agree and our new Reading curriculum is designed to build background knowledge intentionally as students read. But we also know that schools are using it live in the real world. They and their students will still be assessed on their ability to show mastery of reading standards. They can’t ignore that. Does this preclude a knowledge-driven curriculum? We don’t think so. This post describes how standards are addressed in our curriculum and why we think a knowledge-driven curriculum can prepare students to be successful on assessments–and do a better job of it–while also developing their reading ideally for the long term.

The questions we’re asked most frequently about our curriculum have to do with standards. Schools want to know:

- How can we be sure the curriculum is aligned to standards?

- How can we be sure it will build enduring mastery of those concepts?

- How do we know we are preparing students for success on assessments?

- How can we track which standards are mastered or emphasize a specific standard if needed?

While standards may not play the exact role in lessons that some teachers have come to expect, they are still central to our design and are still critical in shaping what students learn. In fact, one of the key reasons we’ve approached standards differently is to ensure that students achieve more effective and lasting mastery. This document describes how we approach standards and why, summarizing some of the important scientific research and outlining some tools for managing standards available to you.

Our Objectives Aren’t Standards

One of the first things you’ll notice about our curriculum is that lesson objectives are text-driven: they describe what we want students to understand about the passage of text they are reading that day. Most likely you will never see the same lesson objective twice. They’re unique to each lesson because they are specific to the passage or text.

That’s different from a typical curriculum where daily objectives describe a general learning standard with no specific reference to the text students are reading that day. Because they’re general they often reoccur. The objective in a typical curriculum’s study of The Giver, say, might read, Students will be able to describe the change in a character’s perspective. That objective might occur several times in the course of reading the book.

A typical objective in our curriculum might be the one for lesson 17 from our unit on The Giver: Analyze how Jonas struggles with the burden and power of his new role in the community. Questions in the lesson ask students to discuss why the Receiver ends each session with Jonas by giving him a memory, for example, or how Jonas reacts to witnessing a release for the first time. We think these questions will help students understand Jonas’ struggle to accept power as described in the objective but we also think critical scenes from The Giver are more than just an opportunity to discuss Jonas’s perspective, and that students are more engaged in reading when the goal is to study the ideas that made the book worth reading in the first place. The story the book is telling should determine the objective.

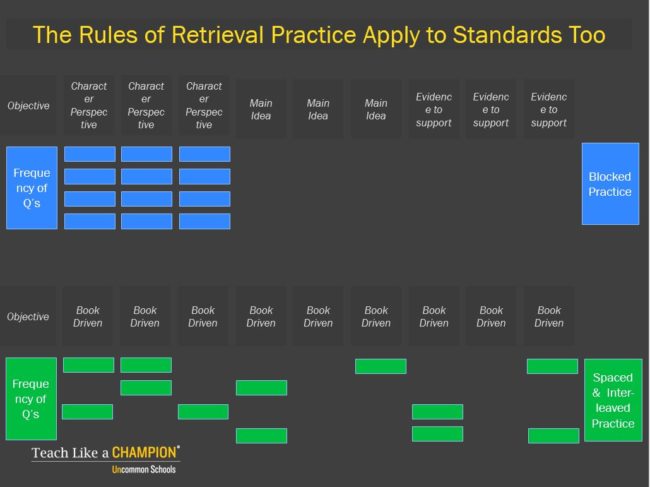

Just as importantly though, research about learning tells us that structuring a series of lessons around a specific objective is a less efficient way to learn–especially over the long run. A wealth of data tells us that students learn skills better and more durably when practice is spaced and interleaved[1]. Practice with a skill has to be spread out, occur in combination with other skills, and occur unpredictably to be optimally encoded in long-term memory. Spreading questions on a given standard out across multiple lessons and ensuring that they occur in different contexts with a bit of unpredictability results in better learning than practicing them all at once.

In addition, text-driven objectives are important because the true test of mastery is to learn when, how, and why to apply a skill in the study of a great piece or writing. To do that students need to apply multiple skills in combination and synergy–not just one at a time–and do so because the experience of reading a book deeply demands it. Understanding the book should determine the skills readers use.

In other words, our approach to objectives doesn’t mean standards aren’t addressed. Our curriculum is full of standards aligned questions*. (It would be all but impossible to achieve a text-driven objective without strategic application of them). They’re just organized to maximize learning, both by allowing for spaced practice and by allowing us to balance their presence with questions that build background knowledge, a factor that cognitive science tells us has a greater effect on reading comprehension even than standards themselves.

*Admittedly some standards aligned questions we ask a lot less frequently. Main Idea is a good example. Most research suggests that 6 or so iterations of that skill provide as much benefit to students as do 30.

[1] See Brown, Roedigger and McDaniel’s Make It Stick, and Agarwal and Bain’s Powerful Teaching for more discussion of the importance of spacing and interleaving.