02.13.15Giving Feedback as a Coach–Isabel Beck and the Secret Life of Guided Discovery

I started thinking about the following while working with coaches during a session for the US Soccer federation—but it also reflects a couple of broader teaching thoughts that have been cooking away for a while. It’s pretty rough–still thinking of it as a draft but i I hope it will be useful to those who work with both teachers and coaches.

Teachers and coaches, and especially as teachers of coaches and coaches of teachers, are often reminded to use guided discovery in feedback- to, in a nutshell, help the person getting feedback to discover for themselves what to do differently through open-ended questions rather than our to TELLING them what to do.

To be honest, I both like and dislike guided discovery.

The reasons for liking it are-

- People often believe in a solution more when they believe they have thought of it themselves.

- You model the process of self-critique.

- You’re never quite sure if your answer is right and, done right, guided discovery leaves room for you to be proven less right than the person you’re coaching.

But the reasons for disliking it are legit, too:

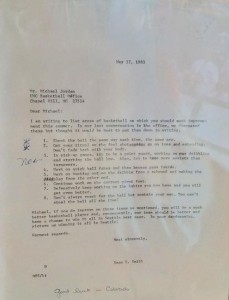

- Sometimes you are the knowledgeable person and the most valuable thing is actually for you to help recipients see something that you recognized. Often that’s why you’re the coach. Often this is what they want–to know how to get better. For example this amazing letter from the late-great Dean Smith to Michael Jordan.

- The person you are guiding can also fail to come up with a useful insight. Or the one you wish to discuss. As a result you and your feedback can appear disingenuous-you ask someone what they thought and then disregard it and talk about something else. Why ask their opinion anyway, then?

- Guided discovery is time consuming and if you have a short period of time to give feedback you are especially at risk of one of the two above issues emerging.

I saw some of this when the US Soccer coaches practiced giving feedback to ‘candidates’ who they imagined had just taught a session in a high level licensing course. Some coaches opted for guided discovery with their feedback and they’d ask questions like “Well, what didn’t players do?” or “What do you think they might not have understood?” or “What else could you have tried?” The session often took a great deal of time to get to an answer that (it was pretty obvious) the giver of feedback, the expert, not only knew all along but had to help the candidate recognize if he or she was going to have a chance to pass the class. Not to mention there was about two minutes available for all of feedback.

The question became, in my mind at least, not “Is guided discovery a useful thing to do?” But rather “Is it the most useful thing to do given the very short time you have available?” and perhaps, “How do you do it well?”

Strangely the issue reminded me, above anything else, of vocabulary instruction- an odd connection for sure but one that reminds me that the rigor of discovering something is often lower than the rigor of figuring out how to use it. This point can, in fact, provide the solution to how to get the best from guided discovery and limit its risks.

I often feel uncomfortable with the vocabulary instruction I see in classrooms. Often it involves a lot of students guessing at word meanings they don’t know in the name of guided discovery. “Can anyone tell me what destitute means?” “No it doesn’t really mean that.” “What else might it mean?” “Yes it has something to do with needing things but it actually means….” There’s a lot of guessing but not a lot of rigor to it.

Isabel Beck’s landmark book on vocabulary, Bringing Words to Llife offers an alternative. She suggests is the work of applying and adapting words is problem solving– more rigorous than guessing at word meanings you don’t really know. Even using ‘context clues’ is deeply problematic. (read about that here). She observes that it is better to GIVE the student the information they need—in this case the definition—and THEN to engage in guided discovered focused around HOW TO USE the word. Not ‘What do you think destitute means?’ but rather, “To be destitute means to be completely without necessary resources. Who’s destitute in the book? Who’s destitute in [name another book here]? How is the nature of their destitution different? Question: could be destitute even if you have lots of money? Can you think of a way that might be true? Good what would you do about it if you were destitute?

To the question question WHAT FORM of guided discovery or at least guided questioning is best most rigorous (and efficient) I tend to side with Beck: application is usually more rigorous than identification, especially when the latter is predicated on knowledge that an expert has and another person needs. This observation is potentially useful to trainers and coaches.

You might, for example, give a person you are coaching a key idea to use and then guide them through a study of its potential applications.

|

Non-Guided Feedback |

Guided Discovery Focused on Inferring Knowledge |

Guided Discovery Focused on Applying Knowledge |

|

|

Teaching Example |

“Student engagement seemed really low.” |

What did you think of the level of student engagement? Why do you think the level of student engagement might have been low? |

One reason student engagement can be low is because students feel like it’s ok to choose not to participate. Some teachers address this through the use of Cold Call… calling on students who haven’t raised their hands. When might you have used that in your lesson? Which questions would have been best to cold call on and how might you have revised them? What would you have needed to do for that to be successful? What might go wrong if you tried it and what could you do about it? |

|

Non-Guided Feedback |

Guided Discovery Focused on Inferring Knowledge |

Guided Discovery Focused on Applying Knowledge |

|

|

Coaching Example |

It looked like players were making a lot of mistakes as they practiced and that you weren’t aware of it in a lot of cases. |

What did you think the level of mastery was? Why do you think you weren’t very aware of the level of mastery in the session? |

One thing that many elite coaches try to so when they teach a new skill is to arrange the physical space so the event they are evaluating occurs in a predictable time or place. Then they set out to track the group’s proficiency level. Can you take that idea and propose some ways it might help you to more accurately organize the physical space to make it so you were better able to observe mastery? What would the most likely errors be and what would it look like if they were happening? Can you think of ways you could actively track the level of proficiency? |

Not saying the right hand column is always right. There’s a time and a place for all three columns. But when people think about questioning with another professional I think they tend towards the middle column and it’s not always as valuable or as rigorous as it could be.

So… perhaps you could take a minute to reflect on some situations in your coaching or teaching when you could make your guided questioning more applied? With whom, when, would the idea work best and what sorts of questions would be most productive to ask of them?

Thank you! I have often thought along the exact same lines, but it has been frowned upon to voice such an opinion depending on which current “new only correct way to teach” in in favor. I sound bitter? I do because so often it seems that teachers are forced to use practices that don’t fit their students’ needs, and it seems that our leaders are always looking for a new teaching miracle that will solve all the problems in education, when actually we need to do the same thing we want our students to do, which is apply what we have learned about educating students in the way that is appropriate, efficient and effective. I love the sense in the realization that rigor lies in applying new knowledge, not in making the student think that they discover everything. Students are far more savy than that. They know when we are conning them. I like the example given about fishing for the right definition in a vocabulary lesson instead of just teaching the definition and then letting the students practice using it. Learners need genuine opportunities to problem solve and practice new skills and ideas. I am not saying that the discovery method is never appropriate, but like every good thing, it should be used intelligently.

I love “Teach Like a Champion,” and it changed the way I teach and I have recommended it to all of my colleagues. I noticed immediate improvement in engagement and results in my classes from the first time I tried using the first five techniques in the book. I actually made a poster for me in my classroom to help me remember to use them. The results were terrific and I didn’t need it for long. If you have not read it, get a copy now; you won’t be able to put it down.

Thanks, Julie. I often find with certain ideas that it’s more about when and how than whether or not to use them. I think this one is a good example. Regardless thanks for your kind words.

Thank you for an enlightening discussion about guided discovery. I think guided discovery will be very useful in some subjects like science. But in other subjects like writing or journalism, it may be more productive for the students if they get told what they need to know first then guide them in application.